Diploma Double-Down: New Orleans’s KIPP Renaissance High School Plans to Graduate the Class of 2020 as Juniors — College Juniors

ByBeth Hawkins

Read the full article at The 74 >

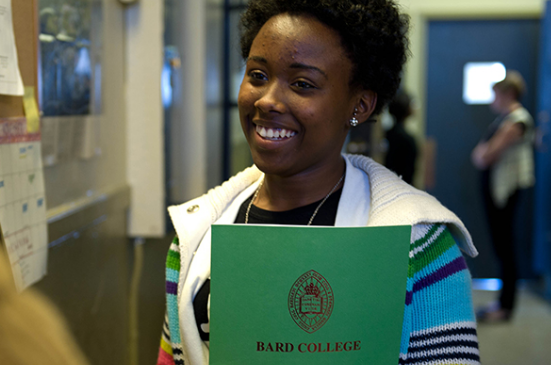

This year, half the juniors at KIPP Renaissance High School in New Orleans are also freshmen at New York’s Bard College. They’re being taught by Bard faculty, all of whom have Ph.D.s, for free, on a Bard satellite campus set up on the high school’s top floors.

Unlike applicants to Bard’s traditional liberal arts college, interested KIPP sophomores don’t need to show a high grade point average or college entrance exam score. Instead, they participate in a college-style seminar where they can display their intellectual curiosity and motivation.

If everything goes according to plan, the students will graduate with both a high school diploma and an associate’s degree in humanities. Their odds of earning a four-year degree will increase tenfold, and the fact that their first two years of college were free will cut the price tag for their mostly low-income families in half.

The move by Bard, a leader in successful early college programs, and KIPP, the nation’s largest nonprofit charter school network, is a natural extension of a seven-year-old partnership between the two institutions. And it’s an example of the kind of ready-for-college program Congress set out to encourage in the Every Student Succeeds Act, the 2015 federal law intended, among other things, to prod states to get more disadvantaged students to and through college.

Under ESSA, states must now track and report how many high school students are enrolled in college-level classes, how many are from historically underserved populations, and what schools and districts are doing to ensure that those students are ready for college.

“It’s absolutely a major shift,” says Lillian Pace, the senior director of national policy for KnowledgeWorks, a nonprofit that has worked with early college high schools for more than a decade. “We’ve seen the bar shift from states exploring to states doing the hard work of making sure students have equal access to these programs.”

Bard and KnowledgeWorks are among five organizations that came together two years ago to promote awareness of the opportunities that ESSA has opened up. The coalition, the College in High School Alliance, hopes to help state education leaders figure out how to take advantage of provisions that encourage creative ways of using public dollars to fund high school college programs.

Other alliance members include the Middle College National Consortium, Jobs for the Future, and the National Alliance of Concurrent Enrollment Partnerships.

While there is debate about how well students are actually able to transfer college credits earned in high school, there is plenty of research showing that exposing them to college classes increases the chances they will enroll in college and earn a degree.

Many states have long offered students the opportunity to take free classes at public colleges and universities. Some have invested in concurrent enrollment, a variation in which high school teachers become qualified to teach college courses within a high school.

In the early college model, students finish the bulk of their high school requirements early and spend their junior and senior years enrolled primarily in college courses, with the structure and support of their high school community.

According to a report issued this year by the advocacy organization Alliance for Excellent Education and the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, minority students who graduate from early college high schools are 10 times as likely to complete a four-year degree as their peers. Low-income students are 8.5 times as likely to obtain a degree, and white students are four times as likely.

In 2001, Bard teamed up with the New York City Department of Education to create the first Bard High School Early College, a public, four-year high school located in Manhattan. Campuses subsequently opened in Queens, upstate New York, Cleveland, Baltimore, Newark, and New Orleans.

KIPP students have been eligible to attend Bard classes on the New Orleans campus since 2011, but the city’s half-day program does not grant a degree. With 224 schools in 20 states serving almost entirely low-income students, KIPP has invested heavily in getting its students into college and, most recently, assisting them until they earn a degree.

“The fertile ground here was a partner that has a willingness to rethink the playbook for the last two years of high school,” says Stephen Tremaine, vice president of Bard Early Colleges. “To do something really ambitious but also structurally difficult.”

The leap of faith, of course, involves money. Because dual-credit programs are often paid for by sending some or all of students’ state per-pupil K-12 dollars to the college where they enroll, some districts have been reluctant to promote the programs.

Pace notes that new federal laws encourage states to experiment with funding the programs. Eight early college high schools are participating in a U.S. Department of Education pilot testing the use of Pell Grants, which are normally reserved for low-income high school graduates.

In the Bard-KIPP partnership, more than 80 percent of the cost of embedding college in high school is paid for with Louisiana per-pupil funds that would otherwise underwrite 11th and 12th grades, says Tremaine. The rest is covered by philanthropic funding.

The model makes economic sense, he says: “With four years of high school and two years of college in four years, then the public investment is less and goes further than four years of high school and four years of college.”

“The reality is, we are a college,” says Tremaine, “and colleges are in the business of finding talent that is going to improve the world.”